A note before reading

We offer reflection questions as an accompaniment to an individual or collective reading of this material. You are encouraged to use these questions to deepen your reading and prayer and to help direct your individual or collective reflection.

In 1829, Mother Duchesne did proceed with this plan, purchasing* an enslaved woman named Rachel. Rachel had originally been sold* for $454 by Cornelius Rhodes to Bishop Dubourg. When Dubourg left Missouri for France in 1823, Rachel remained in St. Louis as housekeeper for some of the priests, who reported ongoing “difficulties” with her in 1825 and 1826. These issues apparently persisted after she was purchased* and brought to the City House (the first Society convent and school established in St. Louis in 1827). Philippine’s letters recount Rachel’s insistence that she was not in fact enslaved to the Society at all. “I think this is a story she has made up out of her own head. We bought her from Bishop Dubourg and paid for her,” writes Philippine in one letter. In another, she complains that Rachel was “not so good anymore” and asked her superior to speak to DuBourg about the question of ownership,* suggesting, “perhaps I will be obliged to ask him for a receipt.” By January 1829, Philippine’s letters report that Rachel’s behavior had “improved.” This improvement apparently did not last, however, and in May of that year, Rachel was sold.*

In May 1830 at the City House, Mother Duchesne wrote in the house journal that a Mr. Dubreuil had “given” them a man named Joseph in lieu of tuition for his daughter. Joseph is probably the one enslaved man who appears for the convent on the census of 1830. The rest of his life is unknown; he was probably taken back by Mr. Dubreuil when his daughter’s education at the school ceased.

On July 2, 1834, there is evidence for one, perhaps two, enslaved men at the City House. Rose Philippine Duchesne wrote to Eugenie Audé, RSCJ, from City House that “the Negro manager is good and renders good service.” He was probably “acquired” from a Mr. Kelly (called “Kely” in the letter) in New York, who returned on business from there in November. The person she references is likely Edmund (see below). A few months later, on October 5, 1834, Philippine wrote to Madeleine Sophie that 4,750 francs were owed for the purchase* of an enslaved couple, “absolutely necessary for domestic service.” She describes the wife’s behavior as so bad that she “was made to pay for her incendiary actions by a few days in jail and the threat of a whipping” and then hired* out to someone else, “of whom she will be afraid.” The woman’s husband, however, is praised as “very good, does errands, the garden, and provides part of the wood.”

Edmund

By August of 1836, Edmund (surname unknown) appears by name in the records of the City House — the first convent and school established in St. Louis in 1827 — described there as a worker for the school entrusted with the work of running errands and carrying messages. In four letters of the new superior, Catherine Thiéfry, RSCJ, to Bishop Rosati, from August 1836 through August 1837, the letters indicate that she has sent them in Edmund’s care, and that he would wait for the bishop to pen his answer before returning. On August 7, 1837, the letter indicates that Edmund had come with a carriage to bring the bishop back to the school. He is probably the one enslaved man listed at the City House in the census of 1840, and likely the husband of the “difficult” woman referred to in November 1838 (see below).

In June of 1840, Edmund went with the four Religious of the Sacred Heart (RSCJ) founders of the Potawatomi mission to Sugar Creek, Kansas. One source says that he was “given” to them at that time by Mother Elisabeth Galitzine, RSCJ, who had come as provincial and visitator from Paris (L. Mathevon, Commencement de la Mission Indienne). Since Edmund was already present at the City House from at least 1836, four years before Mother Galitzine came to America, this reference is problematic. Perhaps in her authority as provincial superior, she transferred him from the City House community to the new one going to the Potawatomi mission. Later in Kansas, Edmund appears in letters described as a skilled carpenter who shared his skills with the Potawatomi and was treated by them in turn with great respect:

Our Negro is most useful to us here. He is a man of importance. He is almost as respected as we are. He teaches the Indians carpentry. They are naturally skillful and easily imitate what they are shown to do. They made a pretty fence around the cemetery, but they did not know how to find the place for the gate. Edmund delivered them from the problem and helped them finish this little project. I am careful not to tell him that he is free here, for, though he is happy and perhaps too devoted to abuse it, it is nevertheless more sure if possible to leave him in his ignorance. The Indians are almost as black as he, gentle by nature, and they all dress very decently.

(L. Mathevon to E. Galitzine, August 1841, USCA).

Somewhat unusually for the time, Edmund appears also to have been literate, because one document recounts that while he was in the nearest town, Westport, conducting errands, he read in the newspaper in January 1844 of the death of Mother Galitzine in Louisiana in December 1843 and brought the news back to the religious. He was legally free in Kansas, though the superior, Lucile Mathevon, RSCJ, wrote that she hid this important information from him. It is likely, however, that he learned it in some other way, and may have claimed his freedom for himself around 1844, after which he disappears from the records and his whereabouts are unknown. The St. Mary’s Mission records in the Jesuit archives contain no information about a marriage or death record for him. Note that the mission at Sugar Creek was near the Santa Fe Trail which passed through Kansas territory and led to Mexico where slavery was illegal and further on to California, also a free state.

Records from Florissant, beginning in December 18, 1836, make reference to slavery, when Philippine wrote to Father Timon, superior of the Vincentians at The Barrens, about 90 miles south of St. Louis, asking his help in securing either a man or a woman to do domestic work, cut wood, and run errands from Florissant to St. Louis. On January 27, 1837, she rescinded the request, citing a presumably free domestic servant who had left them but wished to return, so apparently there were no “acquisitions” through the Vincentians at that time. However, by the following spring, a mention of two enslaved women at the City House appears in a letter from Philippine to her cousin, in which she laments that her poor knowledge of English makes it impossible for her to give religious instruction to “our two Negresses” or to poor children.

The two mentioned in Philippine’s April letter are probably the same two who appear in documents in October 1837 recording the presence of an enslaved woman at St. Ferdinand in Florissant, whose name was probably Mathilde, with a young daughter. According to the records, this woman was enslaved by someone else, who wished to take her back. By November 1, the mother and daughter were gone, and the community lamented that no one was left to cook or care for the cows. The mother and daughter must have returned within a few months, however, because on May 31, 1838, Philippine reported in the house journal that the little daughter, 8 years old, had died. She “was able to make her 1st communion before her death; four of our pupils carried her to the cemetery.” By August 31, three months after the death of her child, Mathilde had left for a second time.

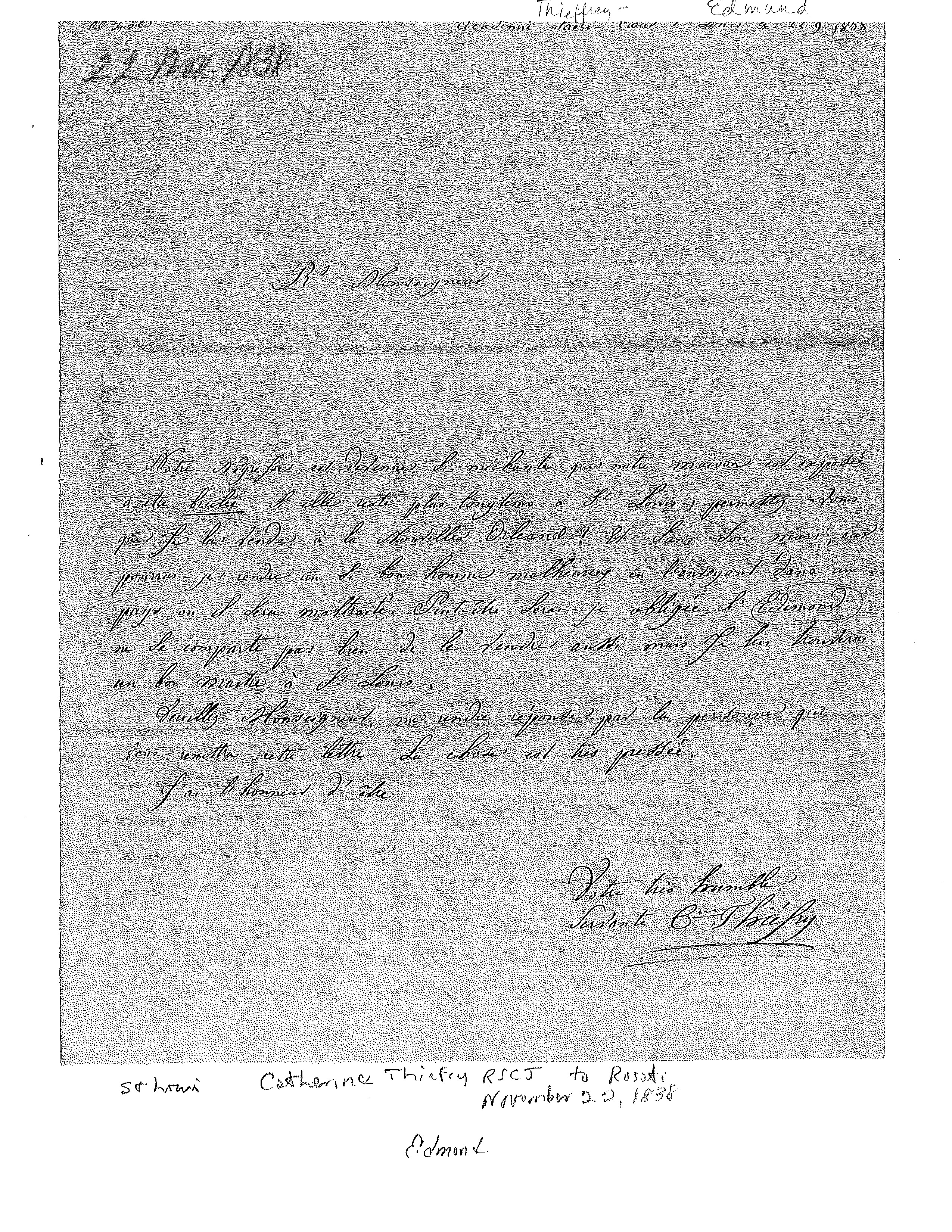

Later that year, in November 1838, another enslaved woman at the City House was described as “difficult”— probably the wife of Edmund, and likely the same woman who was considered “difficult” in 1834. The superior, Catherine Thiéfry, wrote to Bishop Rosati of her fears that this woman would burn the house down. In her letter, Mother Thiéfry asks Bishop Rosati for permission to sell* the woman to harsher conditions of enslavement in New Orleans. “And without her husband,” she insists, “for could I make such a good man unhappy by sending him to a region where he will be mistreated? Perhaps I will be obliged if Edmund does not behave well to sell him, too, but I would find him a good master in St. Louis. ” The whole of what it meant to sell* her south to New Orleans, and whether or not they did so, is unclear. Since the request is to the bishop, perhaps it meant to transfer her to another Catholic entity there.

Meanwhile, in January 1839, Philippine at Florissant was trying to find someone to hire as cook. Failing to do so, she wrote that they had taken a young Black woman on as a domestic servant, but this apparently did not last, as Philippine judged her to be “nothing but more trouble… not faithful and has to be watched about everything.” As they did not trust her alone in charge of the orphans in their care, Philippine described the “sacrifice” experienced by holding evening recreation in the noisy kitchen in order to provide necessary supervision. The woman mentioned may or may not have been enslaved by the Society; her labor may have been leased* from another slaveholder, or she may have been a free employee. Her whereabouts after this reference are unknown.

There were no enslaved persons at Florissant listed in the census of 1840, and one enslaved man listed at the City House, probably Edmund, who then moved to the new foundation in Sugar Creek the next year. The next census reports in 1850 list no one enslaved by any of the three Missouri houses.

St. Charles, Missouri

Evidence is lacking for any direct slaveholding by RSCJ at the convent and school in St. Charles, though there is evidence that several Black women of uncertain legal status interacted with the school to perform services of various kinds, and there is rather lengthy documentation of one of these women being baptized in 1853.

The house in St. Charles, open under Philippine Duchesne only for one year, 1818-1819, was reopened in the fall of 1828 with Mother Lucile Mathevon as superior. The 1830 census for St. Charles identifies only white persons as living at the convent at that time.

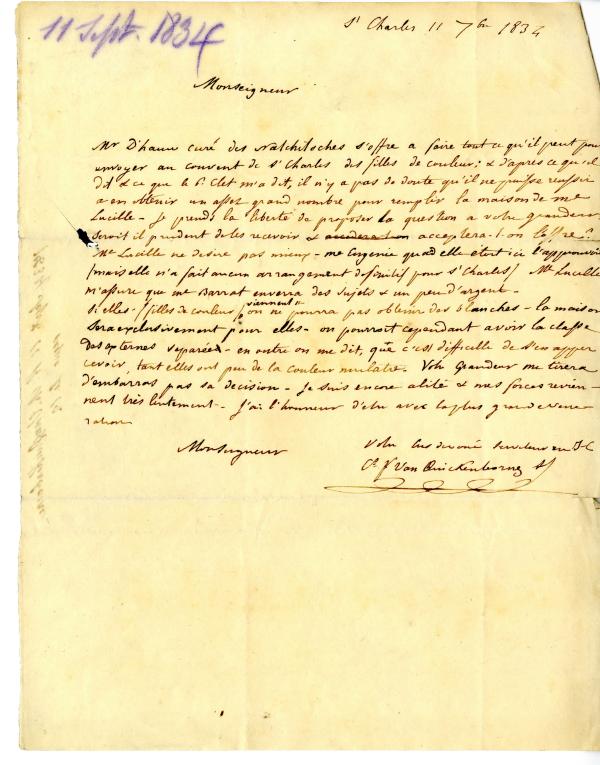

In 1834, a proposal was made to Bishop Rosati in a letter of August 7 by Father Van Quickenborne, S.J., to bring free girls of color (i.e., mixed-race) from Natchitoches to the boarding school at St. Charles. Mother Lucile Mathevon, then superior, was happy to entertain this possibility, and assured him that Mother Barat would send money and personnel. The laws of the day required that even “one drop” of Black heritage would determine a person’s racial identity, regardless of that person’s actual appearance. The enforced segregation of those designated “white” from those of mixed race (referred to as “colored” and “mulattoes” in the 1834 letter), was apparent in Van Quickenborne’s letter, as was the clear social preference and priority given to those whose features more closely approximated whiteness:

If the colored girls come, there will be no question of getting any white girls. The house would be exclusively for the former. However, the school for day pupils could be kept up separately. Moreover, they say you can scarcely notice anything peculiar about these girls, as mulattoes have very little color. (Van Quickenborne to Rosati, September 11, 1834; original ArchStL archives; translation Garrighan vol. 1 pp. 215-216)

The proposed arrangement ultimately did not take place, probably because Bishop Rosati did not approve it.

By 1836, there was an increased need for more help with the work, and Mother Mathevon appears to have pursued the option of “purchasing” an enslaved person to accomplish this goal. In her September 2, 1836 letter to Lucile Mathevon, Madeleine Sophie Barat writes:

… about a Negro whom you seem to need and whom you ask to purchase. If your finances permit you, I am willing, since you have so little help and I can see that you would want it.

This transaction seems never to have taken place. However, beginning one month later, the financial ledger of the house records several entries of payment between October 1836 and October 1839 for unspecified work completed for the house by a Black woman whose name is given (in a July 1838 entry) as Therese. In November 1836, she was given a dress in lieu of payment. She must have taken on more and more work, for the payment increases from $3.00 to $21.00 over that time.

Therese’s legal status is ambiguous in the records. She could have been “leased” from a nearby slaveholder, but in this case it is unlikely that payment would be made directly to her as the records seem to show. Even if enslaved by someone else, she could have been taking on extra work for pay, which was not uncommon. She could also, however, have been a free contractor. She does not seem to be a resident at the convent, as neither the 1840 nor 1850 public records list any persons of color, enslaved or free, living at the convent.

There are no similar financial entries for services in the accounts of the 1840s. On November 9, 1852, a small payment is made, specifically for laundry services, recorded as “for Washing of Black Woman,” and again on January 25, 1853. These payments continue intermittently through July 1854. These are the only evidence for any services provided by a Black woman to the convent during these years, which means that she may be the unnamed woman whose conversion and baptism are described in detail in the house journal of St. Charles for August 23, 1853:

The old black woman in our service for some time previous had the happiness of being baptized and received as a member and child of the Church. The Baptismal ceremony was performed by our Rev. Fr. Verhaegen. She made her first communion the following morning. This poor slave had been fostered in the grossest ignorance and had her mind filled with the most fanatical and abominable ideas to which she was strongly attached, so much so, that she could not be induced to speak to a Catholic Priest or hear anything concerning our holy religion, believing that she had already been instructed by the whisperings of the good Spirit. At length Mother Hamilton charged one of the religious with her instruction and conversion. This poor Apostle was soon given to believe she had been charged with a hopeless and nearly desperate case but yet, trusting confidently in the Father of Mercy and the Refuge of Sinners, she daily implored assistance and light for her poor blind one. In the anxiety she felt she prostrated herself at the feet of Mary, the sinner’s Refuge and besought her to obtain the grace and effect the good, which was beyond her reach. We have no reason to think that Mary did not charge herself with this benighted soul, for by little and little we perceived her incredulity vanish and room left for more saving ideas. Her disposition became daily more and more tractable and the whole tenor of her conduct much more agreeable. She now became as remarkable for her docility to instruction as she had previously been obstinate in her erroneous notions. She gave strong proof of the sincerity of her conversion and great hope for her perseverance. Thus we are given at the same time the consolation of seeing another straying sheep enter the fold of Christ and a new and striking proof of Mary’s Mercy and love towards sinners.

“In our service for some time previous” does not coordinate with the total lack of census or other evidence for the presence of an enslaved woman in 1850. However, “in our service” could also mean hired work, such as that indicated by the financial records. She is described here as “this poor slave,” so she may have been enslaved by someone else and her work “leased” from the slaveholder. However, “this poor slave” could also refer to former conditions of enslavement, or even to spiritual enslavement to her former beliefs. In any event, the emphasis in the narrative is on her gradual acceptance of baptism. She seems to have been quite independent in her religious convictions.

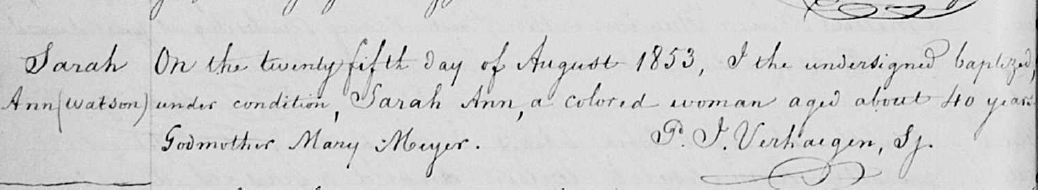

Who is this unnamed woman? She is probably not Therese, who was recorded as working for wages in the 1830s. She is more likely to be the washerwoman recorded as receiving payments for her labor between 1852 and 1854. In the St. Charles Borromeo parish register, a baptism is recorded of a Black woman named Sarah Ann (Watson), age about 40, by Father Peter J. Verhaegen, SJ, on August 25, 1853 (a discrepancy of two days from the house journal account). (Baptisms 1851-1891, page 8. St. Charles Borromeo Parish, St. Charles, Missouri). It is likely, therefore, that the woman described in the house journal account is the same Sarah Ann Watson.

The parentheses around the family name “Watson” would generally indicate the name of a slaveholder. On the slave schedule of 1860 for St. Charles, there is a slaveholder named Martha Watson, who is listed as holding one woman, age 50, in slavery (ages in these records are approximate). In the census of that same year, there are no enslaved persons recorded at any of the convents in Missouri or Kansas. In 1870, Sarah Watson, a Black woman born about 1814, appears in the census for St. Charles, living independently. Nothing else about her is known.

Researched and written by Carolyn Osiek, RSCJ, with collaboration of Maureen Chicoine, RSCJ, and Emory Webre.

References

Arch StL. Archives of the Archdiocese of St. Louis

Duchesne, Philippine. Journal of the Society in America. USCA

Garrighan, Gilbert J., S.J. The Jesuits of the Middle States. 3 volumes. Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1984

House Journal, St. Charles. USCA

Mathevon, Lucile, Commencement de la Mission Indienne. Manuscript, USCA